Protestant Reformation

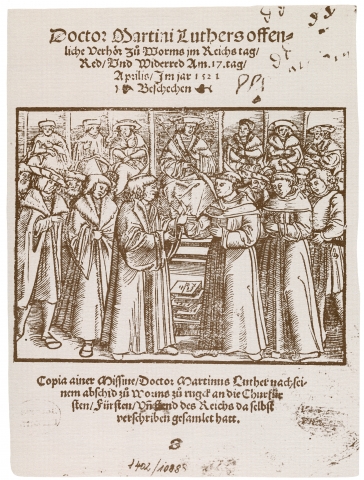

On October 31, 1517, the Augustinian friar Martin Luther (1483-1546) challenged his Church with a Latin list of 95 statements against the late medieval practice of purchasing indulgences to free oneself from the burning fires of Purgatory for falling into sin. These theses were intended solely for internal debate. Intent notwithstanding, the trade in exemptions from punishment proved to split Catholicism between loyal traditionalists and unrelenting critics on this and other theological matters. By virtue of hindsight, we can see today that Luther's act launched a religious movement that we refer to as the Protestant Reformation and that provides a distant ancestry of many of the hundreds of denominations that characterize American religion today. During 2017, five hundred years after Luther’s act, we will look back and assess the causes and effects of his and others' acts.

Luther’s criticism was part of a widespread Roman Catholic self-examination that one can trace back to the fourteenth century and the careers of men like John Wycliffe (ca.1320-1384) in England and Jan Hus (ca.1369-1415) in Bohemia (today the Czech Republic). Sincere spiritual motivation combined with princes’ and magistrates’ desire to curtail the exemptions from taxation and local legal jurisdiction that ecclesiastical personnel enjoyed. The printing press with movable type, invented in Mainz around 1454, made the literature of fault-finding available to a larger audience, including some laymen, and may have helped to coordinate an anti-Church agenda. The literary and cultural trend moving northward from its Italian cradle, called the Renaissance, encouraged learned men to study key works such as the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers to determine whether what the Church taught and practiced was truly in accord with these foundational authorities.

Luther and the Swiss secular priest Huldreich Zwingli (1484-1531) were but two individuals who almost simultaneously began to take decisive actions that could not be undone. They quickly emerged as the inspirers and leaders of cohorts that, once the die was cast, could not be reconciled with the Church. Each man in his respective sphere began to develop a nonconformist theology and liturgical program. These clergymen agreed on two fundamental precepts: that the Scripture contained the sum total of the truth about Himself that God desired His human creatures to know; and that no person could be saved by performing pious works but exclusively on the basis of faith in Christ’s Atonement for humans' sin–that justifying faith being God's gift to only a few, His elect, whom He had designated from all eternity. These two principles, along with many less central ones, were seen by Church leaders as incompatible with Catholic conviction. Luther and Zwingli were able to establish themselves as the leaders of new Christian denominations by virtue of the cooperation of the secular powers (the electors of Saxony; the city council of Zurich). Other theologians in other cities and territories followed suit in due course. Nonconformists who had no governmental backing, such as the Anabaptists (believers in adult baptism), suffered severe persecution, even execution. Reformation currents quickly spread beyond the German-speaking lands to Scandinavia, England, Francophone Switzerland, France, Eastern Europe, the Netherlands, and beyond.

By mid-century, the Catholic imperial forces declared war on the German "heretics" and defeated them. Nonetheless, Protestant identity was by then firmly established and could not be rooted out. Catholic reformers, many of them from the new Society of Jesus and the Capuchin Friars Minor, now undertook to provide new foundations for the traditional faith. Taken together, they had a good measure of success. The decrees of the Council of Trent (1545-47; 1551-1552; 1562-1563) reinforced the doctrinal fundament of the Catholic Church. Both Protestant and Catholic leaders shared a mood of close moral supervision and discipline of society, including peasants, urban laboring classes, and women.